Water Filtration Methods: Mechanical, Chemical, and Biological

Andrew

January 07, 2026

#biologicalfilter

#carbonfilter

#filtertypes

#sedimentfilters

Andrew

January 07, 2026

#biologicalfilter

#carbonfilter

#filtertypes

#sedimentfilters

- Break down the three primary types of water filtration and how each one works to remove different contaminants.

- Explain mechanical filtration (physical barriers), chemical filtration (adsorption), and biological filtration (living organisms).

- Help you identify which water filter types match your water quality needs.

When you turn on your tap, the water flowing through has passed through multiple filtration stages, each using a different method to remove specific contaminants. For most Americans, it all starts at a water treatment plant to clean it up and make your drinking water microbiologically safe. And the process continues at the point of entry, where many homeowners reduce debris and organic matter collected along the way or polish the water of the chemicals used in municipal treatment.

Water filtration falls into three primary categories: mechanical, chemical, and biological. Each method targets different contaminants using distinct principles, and most effective types of water filtration systems combine two or more of these approaches. Understanding water filtration methods helps you choose the right types of water filtration systems for your home.

Mechanical Filtration: Physical Barriers

Mechanical filtration (sometimes called physical filtration) works exactly like it sounds: it physically strains particles from water as it passes through a barrier. Think of it as a sieve for your water, catching anything larger than the filter's pore size.

Sediment filters use mechanical filtration to trap visible particles like sand, silt, rust, and debris. These filters are rated by micron size. A 100-micron filter catches particles easily visible to the naked eye, while filters rated below 40 microns or so remove microscopic particles you can't see. Screen filters, bag filters, and pleated cartridges all rely on this mechanical barrier principle.

Modern innovations have pushed mechanical filtration to the molecular level. Ultrafiltration membranes (0.01–0.1 microns) remove bacteria and some viruses, while nanofiltration (0.001 microns) captures even smaller molecules. Reverse osmosis represents the ultimate in mechanical filtration, with membrane pores at just 0.0001 microns, a size barely larger than water molecules themselves.

The beauty of mechanical filtration is its simplicity: larger particles get trapped, cleaner water flows through. But it only addresses what it can physically block, which is why most systems pair it with chemical methods.

Chemical Filtration: Adsorption and Ion Exchange

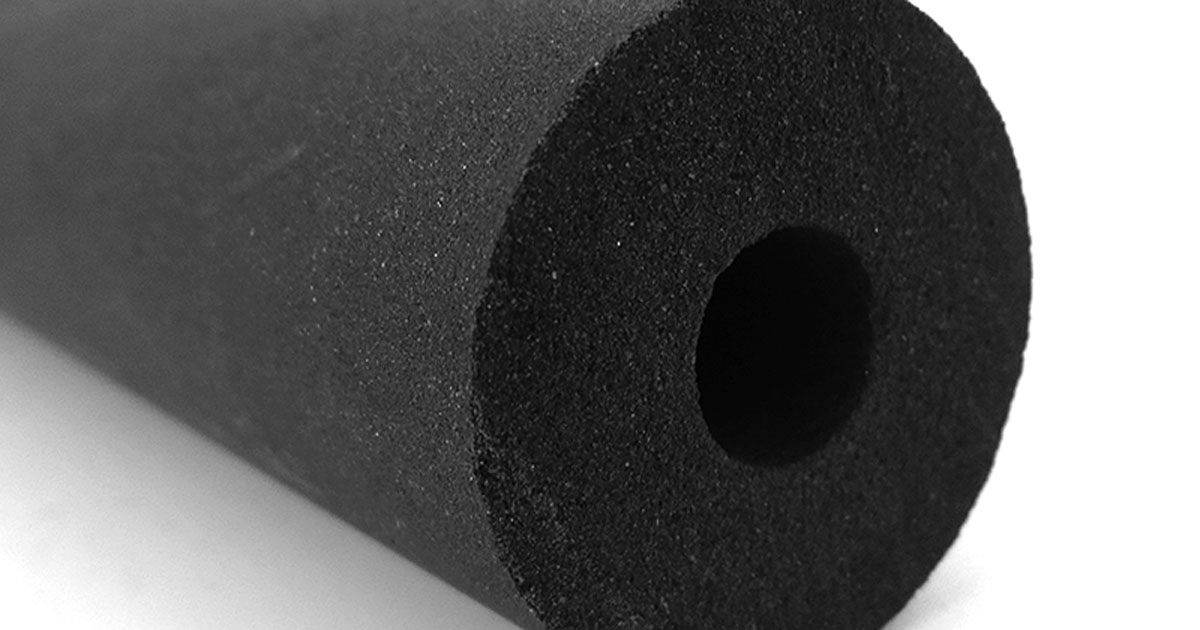

Chemical filtration removes dissolved contaminants that slip right through mechanical barriers. The most common form uses activated carbon, which works through a process called adsorption, not to be confused with absorption.

People often compare activated carbon to a sponge soaking up water, but the sponge analogy is tricky because those little wonders technically do a little absorbing and adsorbing in a process known as sorption. Adsorption is more specific: contaminants stick to the carbon's surface, almost like a magnet attracting metal filings. However you think of it, the carbon doesn't "soak up" the contaminants. It traps them on its surface area through molecular attraction.

And "surface area" is the key term, because activated carbon has a massive surface area. A wee teaspoon of activated carbon can have more surface area than a football field. That's about 4,000 square meters according to research published in materials science journals. All that area creates millions of comfortable sites for chlorine, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), pesticides, and odor-causing chemicals to take their molecular attraction to the next level and form a lasting bond.

Advanced forms of chemical filtration include catalytic carbon filters, which uses enhanced adsorption to target chloramines and hydrogen sulfide, and ion exchange resins that swap hard water minerals (calcium and magnesium) for softer sodium or potassium ions. These innovations continue to push the boundaries of what chemical filtration can remove.

Biological and Other Filtration Methods in Water Treatment

Biological filtration uses beneficial microorganisms to break down organic contaminants and pollutants. While common in aquariums and wastewater treatment, biological filters aren't typically used in residential drinking water systems. These living filters create biofilms where bacteria consume organic matter, effectively "eating" certain contaminants to purify water.

Common biological filter types include bio-sand filters (slow sand filters with a biological layer), trickling filters used in municipal wastewater treatment, and aquarium or pond biofilters that maintain healthy aquatic environments. In developing regions, rural areas, or even emergency situations, bio-sand filters can provide low-cost water treatment, though they require careful preparation and maintenance to keep beneficial bacteria alive.

Beyond the three main categories, other water filtration methods include physical disinfection through ultraviolet (UV) light. UV systems don't filter water mechanically. Rather, they use special wavelengths of light to disrupt microorganism DNA, preventing bacteria, viruses, and parasites like Cryptosporidium from reproducing. UV provides a chemical-free disinfection layer, though it requires pre-filtration since particles can shield microorganisms from the light.

Understanding water filter types helps you build effective filtration systems. Mechanical filters catch sediment, chemical filters remove dissolved contaminants, and UV disinfection neutralizes pathogens. Each water filter type plays a distinct role in delivering clean, safe drinking water.